Faces

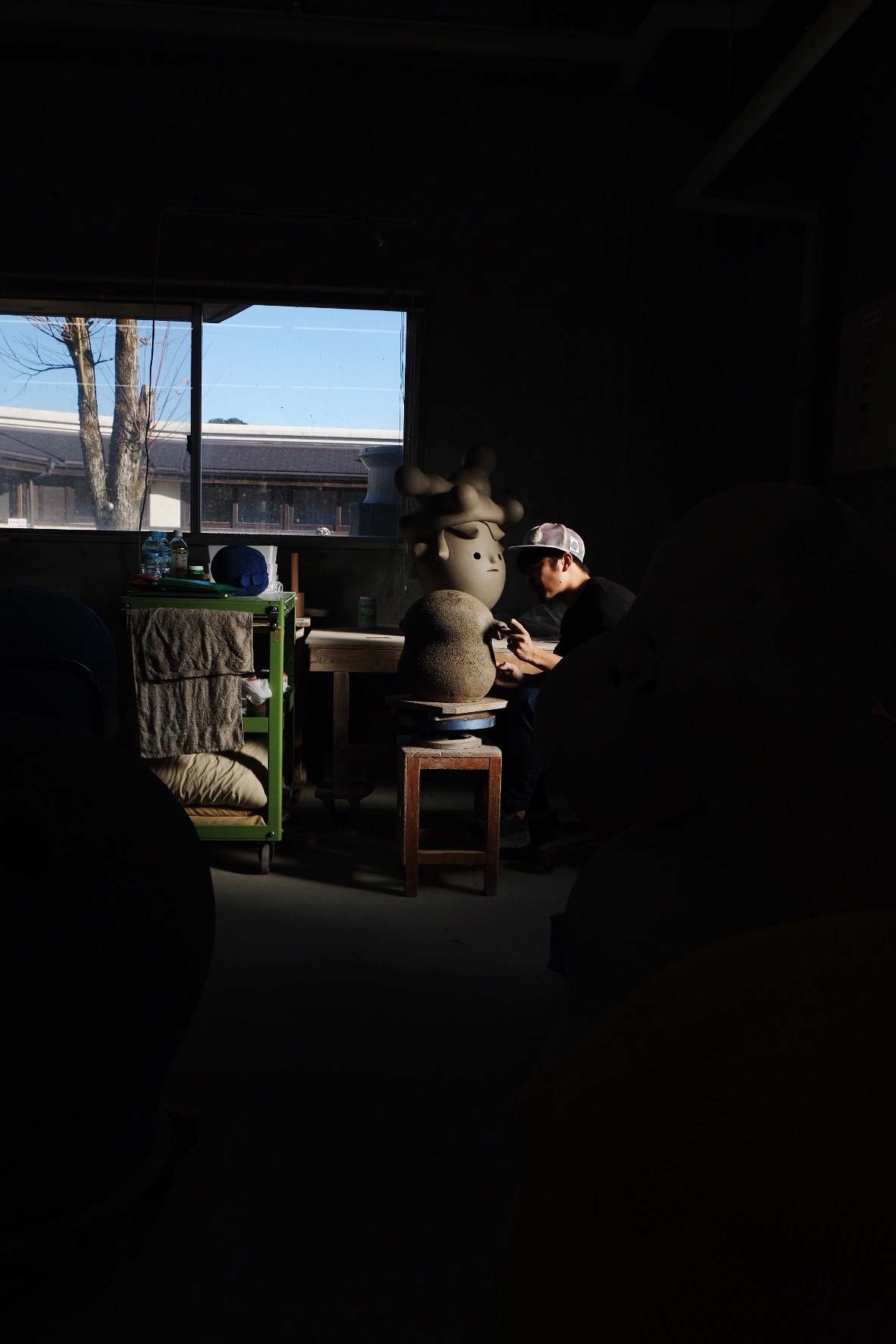

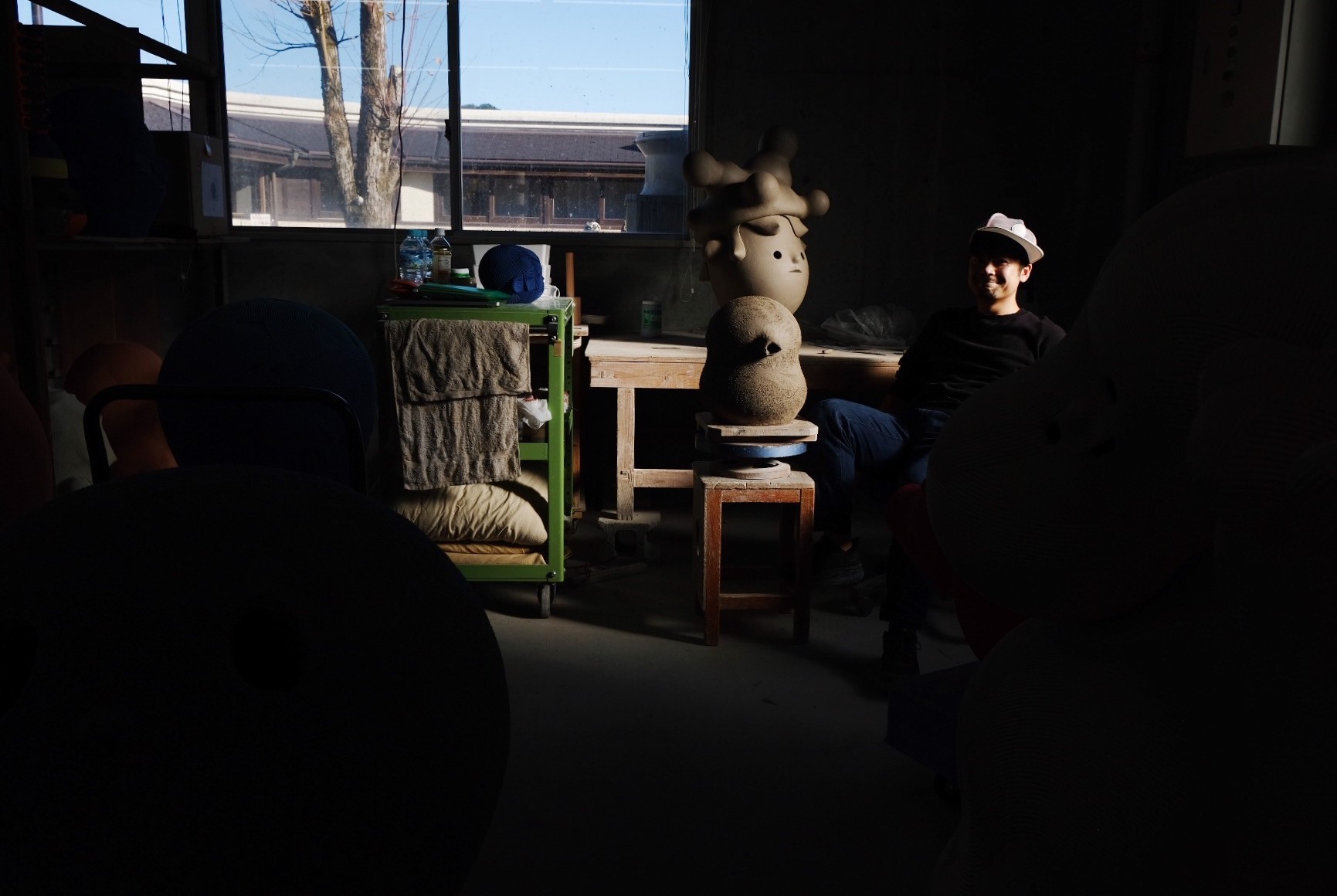

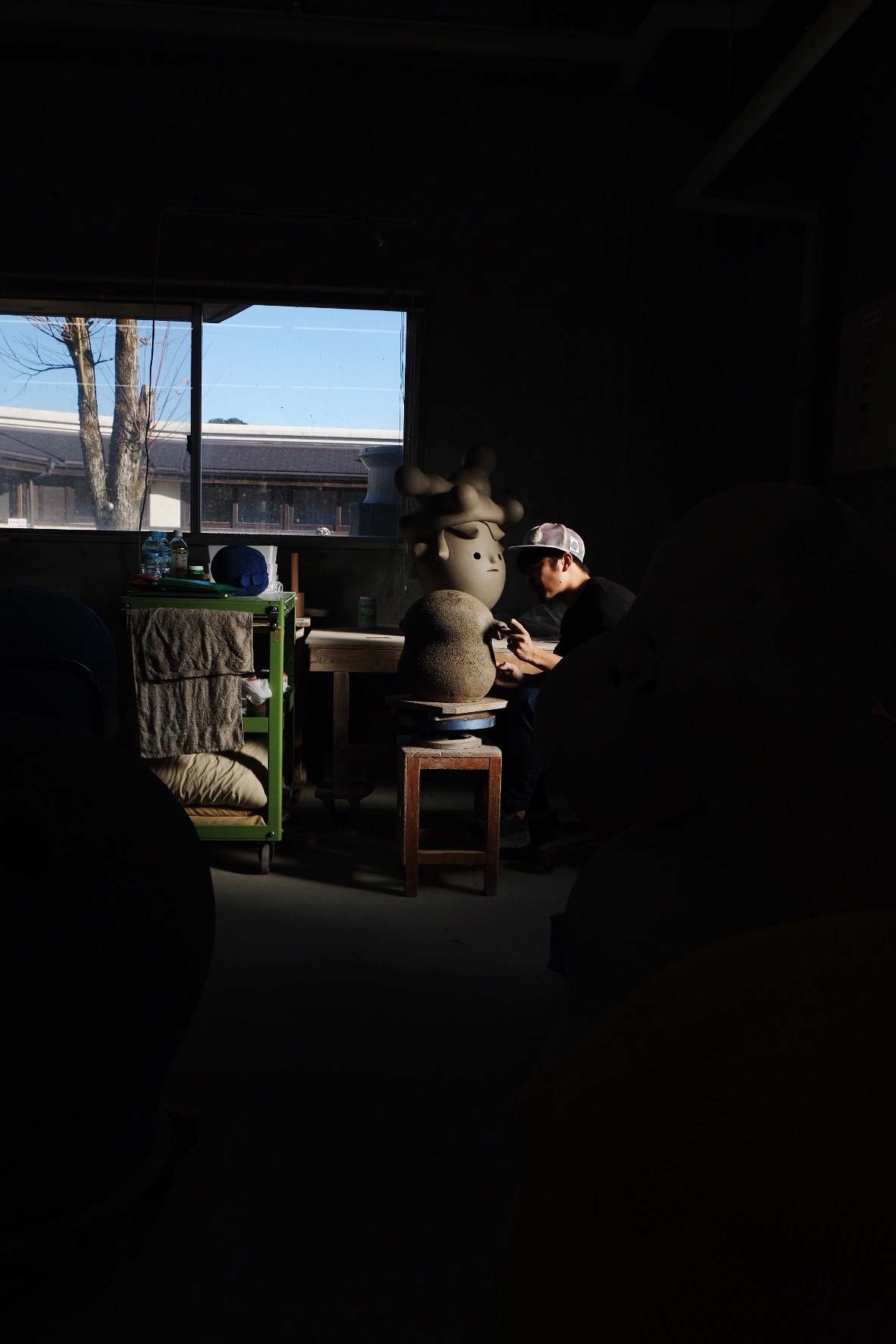

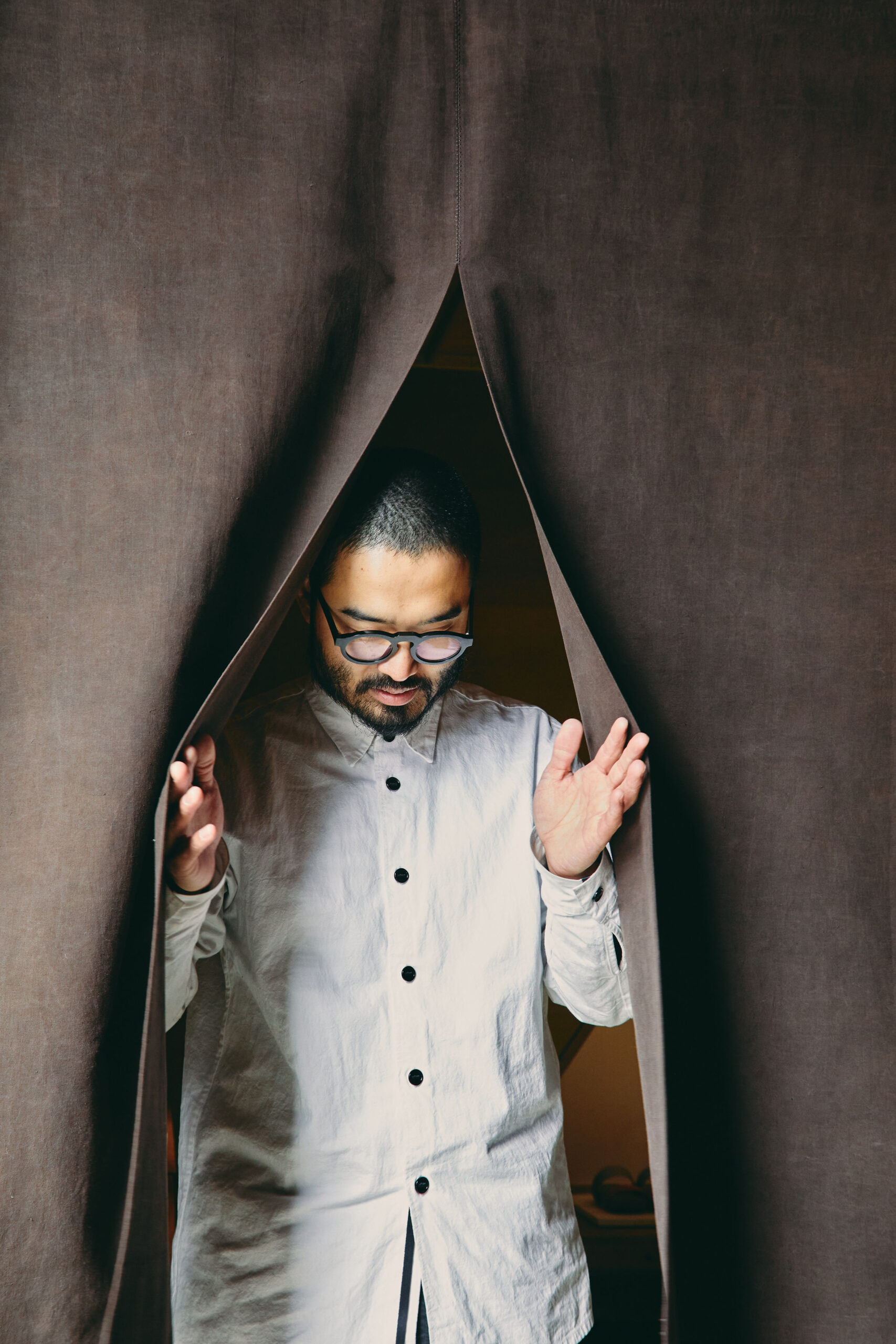

En Iwamura- Artist with no borders

KYOTO

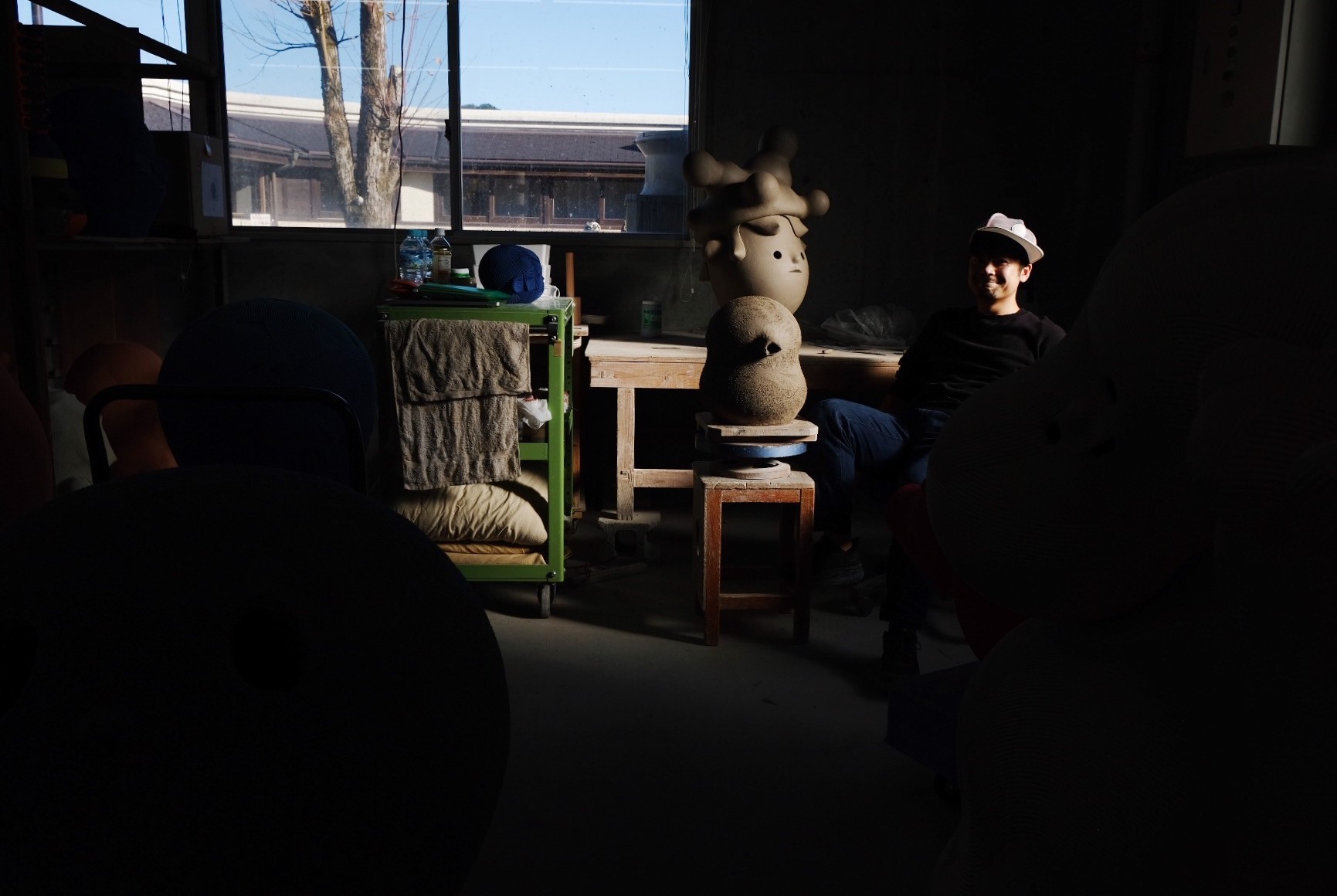

Meet En Iwamura, an artist from Kyoto, Japan, whose creations have captured the hearts and attention of many around the world— including some famous global artists. En is playful, warm, and fun, yet when you speak to him you realize that just like his eye-catching pieces there is so much more depth to him beneath the surface. His work, which is influenced by traditional Japanese artifacts such as haniwa burial figures, explores the Japanese philosophy of “ma” and cultural communication, and Curated Kyoto recently had the chance to speak with En about his work, his creative journey, and even the world of digital marketing.

Words: Sara Aiko

Creative Direction: Sara Aiko

Photos: Sara Aiko

SA: First of all, thank you for letting me visit your studio. Could you please introduce yourself and tell us what you do?

EI: I’m an artist. I don’t like to say I’m a ceramic artist. I just want to say that I’m an artist and I work internationally. Because, you know, if you say “ceramic artist” it feels limited and smaller. I feel a little bit caged.

SA: How did you get involved with ceramics?

EI: That’s a long story, [laughs] but my parents are artists. They met at art school. I had my first exhibition when I was three. But since my parents were artists and I grew up in an art-rich environment, I actually had no idea what art really was because it was so natural to me. I couldn’t define art.

SA: Do you think that was a good or a bad thing?

EI: It was a good thing, because it made me curious. I went to an athletic high school, but for university I wanted to go to an art university. I applied as a painting major at an art school in Kyoto because both of my parents are painters… I didn’t pass the entrance exam. I was so close, but I couldn’t…

SA: Wait, what? How is that even possible?

EI: I’ll tell you what happened… There are three parts to the exam. One is pencil drawing, the second is acrylic with colour, and the last one is sculpture. It was maybe a two or three hour exam, but I finished with a lot of time to spare. I was so confident that I had passed that I decided to clean my space, when…. My elbow knocked the sculpture and it fell. It was destroyed.

SA: Nooooooooooooooo…

EI: My sculpture fell and I failed [laughs].

SA: I mean, couldn’t they just overlook it and say “shou ga nai” (“it can’t be helped”)?

Ei: No, no, it doesn’t work like that. I think I scored like 15 out of 250. But, you know, it was okay, because I kind of wanted to apply to a public art school. There are only five public art schools in Japan, and because of the timing I could only apply to Kanazawa College of Art . I got in… but at the same time I was like “okay, industrial design, what does that even mean?” I was into art, but crafting was a whole new world to me. But it turned out to be so fun. I could touch all these different materials like textiles, wood, urushi (lacquer), and metalware… Of course, I found clay really interesting.

SA: That’s amazing. It almost feels like all these things happened but then your determination led you to where you are now. Who were your earlier influences?

EI: My early influences definitely still impact my work. Influences such as children’s book… every night my parents would read books to us and I was so fascinated by the colours and the fantastic imaginary worlds. But like many other children I also loved shows like Mega Man or Gundam. Superheroes like those were my favourite, but I also loved monsters. Monsters are great.

Another huge influence was working as a gardener’s assistant. I was working with a famous gardener in Kyoto, but also in Nara as well. Working in gardens really gave me a good perspective about space. It was so fascinating and also so beautiful. I really liked it. It made me think about scale and space— especially negative space. How the space exists between objects is such an important thing to think about.

SA: How did your style come about?

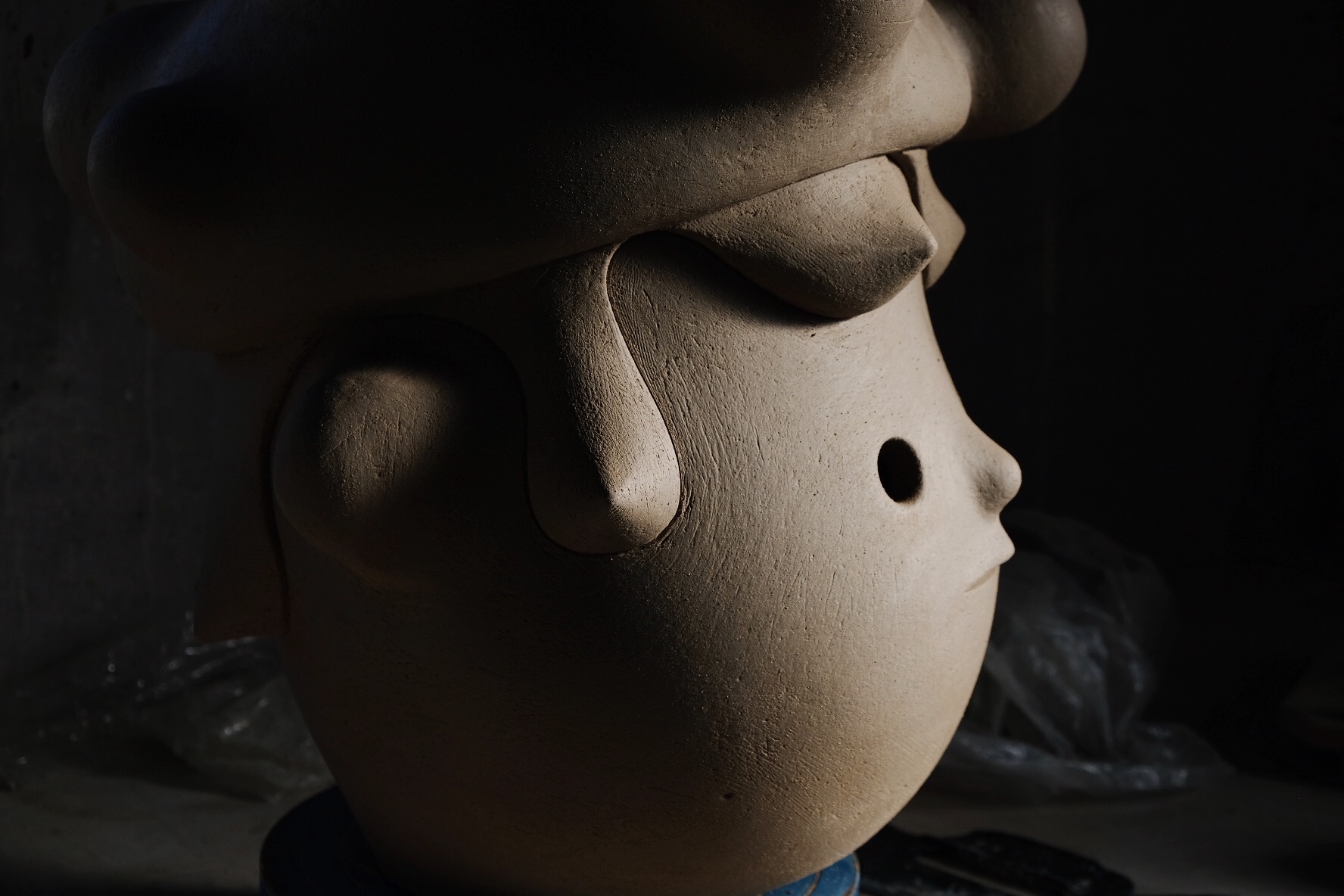

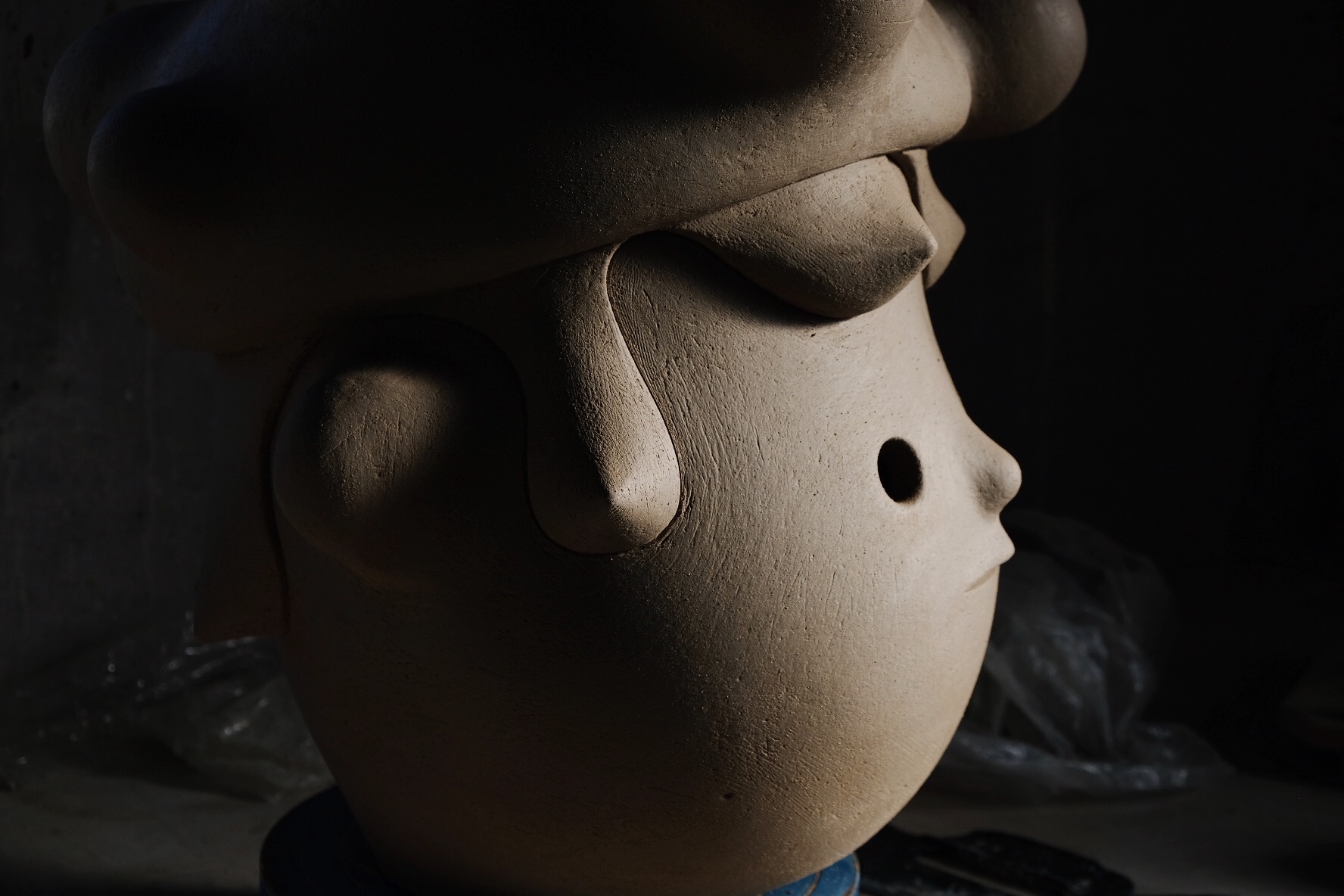

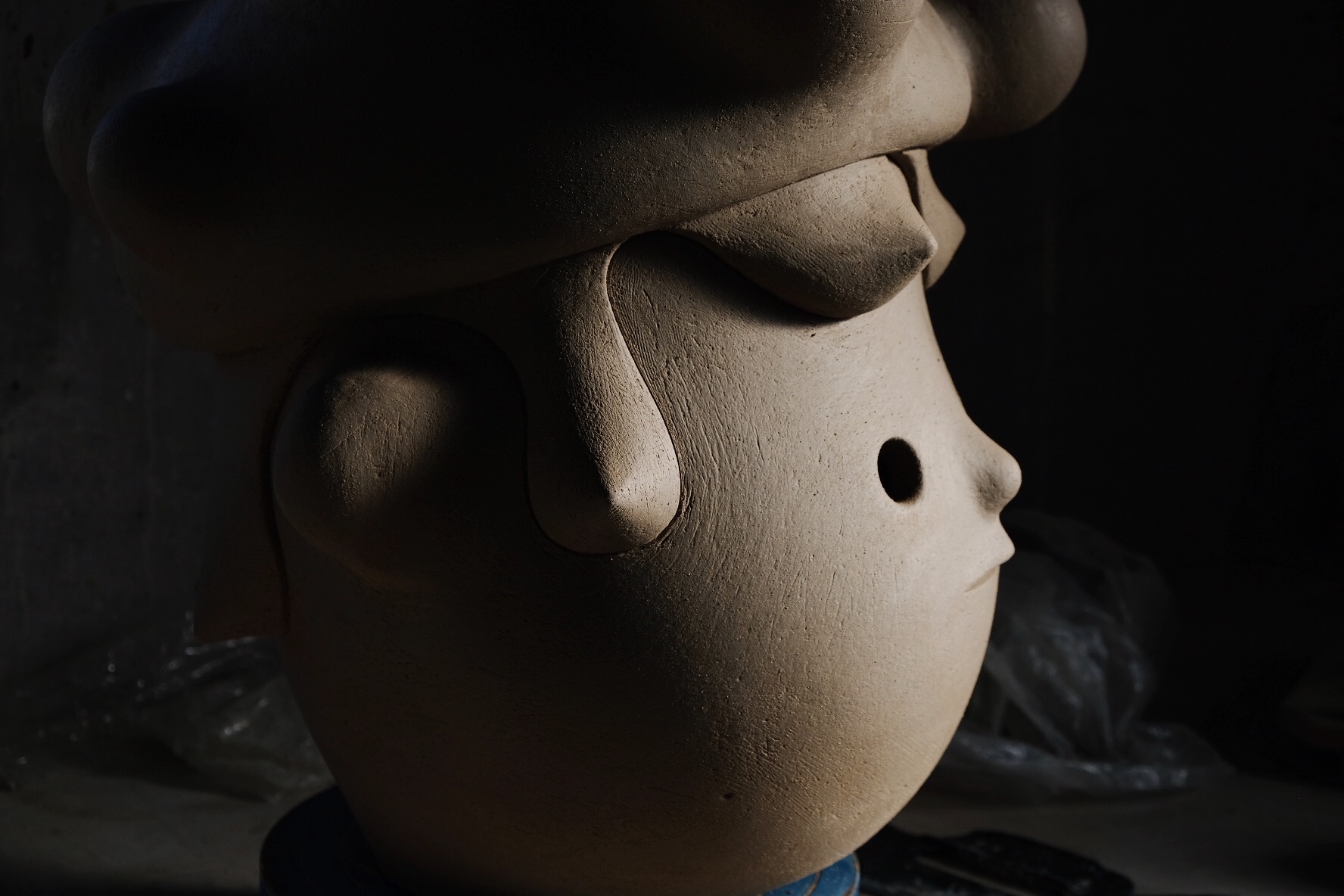

EI: Well, as you know, I was really interested in a lot of styles, but since I ended up studying at one of the most famous ceramics residencies in the US, I thought I should focus on ceramics only. From there, I researched ancient ceramic figures like haniwa and traditional culture since it’s my heritage. I wanted to use ancient Japanese figures as contemporary ceramic art. I first created this alien haniwa, but it was also a pop culture reference.

SA: What kind of message are you trying to convey through your work?

EI: “Culture” is such an important word for me. Because I grew up in Japan, I felt so different compared to other American people when I was in the US. Once I came back to Japan I didn’t feel like this was home any longer because I went to explore and got to know other cultures. When I went to the US again for vacation, I didn’t feel like I was American…. It feels like I’m always standing between cultures. I’m naturally absorbing Japanese culture because I’m Japanese, but when I’m in the US, American culture is such a strong influence on me. So I’m constantly surrounded by different information, but at the same time I’m cultivating my own culture. So in the end, “culture” is not a single word or something defined by area. I think culture is something I made myself… like a filter, so I wanted to create my own “cultural object”. That’s why I created my own personal archaeology.

SA: It seems like colour plays an important role in your current style. It’s changed from your past work, which had more of a natural colour scheme.

EI: With my old pieces, I was intentionally making pieces that looked ancient. Then I realized I didn’t need to make fake archaeology, because my work is going to become an actual artifact in the future. So I thought I should use a strong component of colour in my work to represent the now.

SA: Who are your current influences?

EI: Manga. I have so many manga. Osamu Tezuka, Shigeru Sugiura… It’s old, but his work is so nonsensical and good. I kind of directly use those iconic manga faces in my art.

One person who really pushed me to go to the US was Jun Kaneko. He’s Japanese, but he lived in the US for over fifty years. The scale he works with really showed me the possibilities of clay. He’s amazing. He is super, super famous in the US, but it seems like not many people know about him in the Japanese art world. I find that interesting. He also emphasizes the importance of “ma”, of space. Not just space, but the space between the objects.

SA: Yes, that’s what I was going to ask you. “Ma” is space, but how does that relate to harmony?

EI: “Ma” is not just space. I want to describe “ma” as Japanese philosophy. We are living in the ma. Ma is not just about space and objects, the relationship is also ma. Ma exists between one thing and another, but also between moments in time. People are always living or measuring the ma that they feel comfortable with. Everyone has a different measurement and what feels comfortable to them. I really want to think about the importance of negative space or ma with my works. I want to change the concept with my works. Does that make sense?

SA: Yes, it does. I mean, with “ma” and “space”, what we feel comfortable with in Japan differs from Western culture. Since humans don’t really have close contact with other humans in Japan, we have a lot of space in between the relationships we have with each other. I feel that translates onto Japanese aesthetics.

EI: Yeah, this is why I was so fascinated with the gardens as well. The garden stone placement was so unique and artistic for me. You know how western style gardens are always controlled? It’s symmetric, the placement is calculated… When I worked under the garden master Furukawa-san, it was so magical. Every morning we’d start with a cup of coffee and then we would go out to the garden. There was no blue print. He would look at the garden and be like “okay, could you please place this stone over there?” We would carry these heavy stones and then he would be like “hmm, okay, a little to the left and then tilt it”. Since there were no plans we didn’t know what to expect, but the end result was always magical. It was done with his senses and feelings. He just knew how to measure the ma. I wanted to use that style in my work.

SA: I saw that your work at Ross Kramer gallery sold out in a flash! Congratulations! There are talented artists and artisans in Japan who struggle with promoting their work, but it seems like the whole world knows you. … Obviously that’s because your work is amazing, but how did you promote your work to get yourself out there?

EI: How did I learn? Maybe one of the reasons was my environment. In the US even students think about the market very seriously. Not just about the art market, they think about how they can communicate with society through their creations. In the US, people say that it’s very important to have many different hats as an artist. When we had to go to these conferences, students had to raise our own money. That’s such a wonderful project, because they raise the funds and participate in the conference themselves. The school will help, but they never say “you should do it in this exact way”. We were made to think for ourselves.

SA: Is this an element that is lacking in Japanese art schools? Do you think that art students here could benefit learning it, too?

EI: I think it would be better if they could. If I could teach this here, that would be quite interesting. As a Japanese person in the US, it was such an “aha” moment. It’s like… they do it so naturally, but it’s so important. I had the epiphany that I should make my own website. I was always a net geek, so it was like a game for me.

SA: So, is that how you came up with using Instagram to get your work out there?

EI: Yes, that’s how I used Instagram. I started to use it seriously to promote my work when I started my residency. When I was in school, I was testing how to use it, but I wasn’t that efficient. Once I moved to the artist residency, I realized I needed to use that opportunity to get my work out there, since the residency already had a large audience. I even examined how to use hashtags and what time of day I should post.

SA: So, last question… What’s coming up for you?

EI: Well, because of COVID-19 I’m not one hundred percent sure, but I have a solo exhibition at Ross Kramer. Hopefully March, hopefully May, hopefully sometime this summer? It was supposed to be this March. I just sent a piece but when the coronavirus numbers surged it shut down the city, so I couldn’t have any shows this past year.

One exciting thing is creating my studio here in Shigaraki! I love this city, and it was important for me to have the studio here. This area has a lot of history, but there’s not many young people around. I want to bring a different energy into this space. With places like Nota Shop and the Shigaraki residency bringing in a similar generation of artists, I believe we can breathe fresh air into this community while still living and working with the more mature ceramic community.

SA: Okay, final question. What was one lesson you learned from COVID-19 this year?

EI: Lesson? It taught me the importance of being able to travel and meet people. To value that, and not take it for granted. When we lost the ability to physically travel, we remembered how precious it is to see things in real life. The kanji character for my name, En, means “far distance”. My parents gave me this name because they hoped I would go far away and travel to see things with my own eyes. They believed you should feel things and form your own experiences. I really like my name. I should really live up to that name. And also, that is why I travelled and went far away. If we weren’t dealing with the coronavirus, my father just retired and he’s not really in good health, so I wanted to take him somewhere, like Arizona. I really wanted to show him the real scale of the grand canyon. Let him see it with his own eyes. He gave me the opportunity to travel, so I wanted to share that experience with them. I’m still dreaming.